Vocalizations

The Voice as a Tool

Prairie dogs have a wide repertoire of vocalizations, and ongoing research has sought to understand the nuances of every sound these little rodents make during the course of their day – from territorial calls to barely-audible chirps between mothers and babies, to mating calls and alarm calls. As colonial animals, prairie dogs use their strong voices to communicate to clan or coterie members. Territorial calls reinforce boundaries; a squeak may communicate displeasure, or may be a mother's signal for her offspring to follow her; and alarm calls expose threats to the unawares. Communication is key to efficient colonial living, promoting unity while maintaining social parameters.

The Jump-Yip

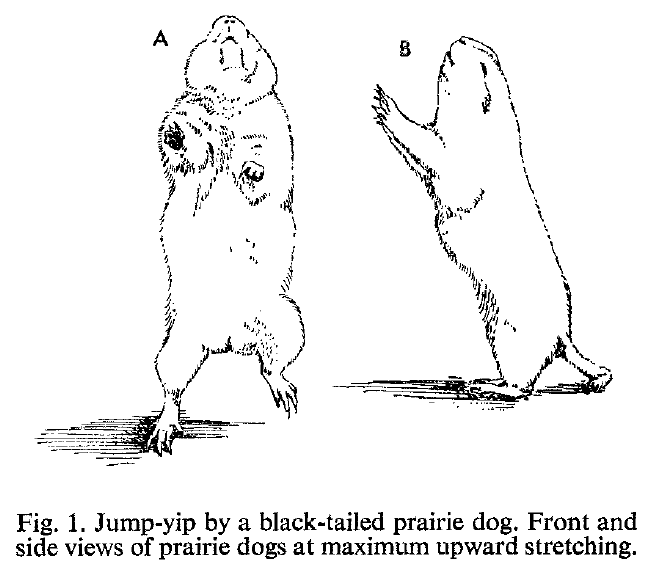

We would be remiss not to pay special brief attention to the famous "jump-yip" call of the black-tailed prairie dog (BTPD). This is a unique display performed by BTPDs and, although less studied, in Mexican prairie dogs as well. As the name infers, the display is both visual and auditory, in which a prairie dog jumps upward off its front feet, stretches vertically, and lets out a distinct two-toned bark described as an "AH-aah" or "EE-eee".

Figure from W.J. Smith, S.L. Smith, J.G. Devilla, E.C. Oppenheimer. 1976. The Jump-yip display of the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus). Animal Behavior 24:609-621

The jump-yip appears to be a multi-purpose communication display, but is specifically associated with some type of threat or disturbance, though it is not to be confused with an anti-predator/alarm call which is given when a predator is present and danger is imminent. The jump-yip may communicate alertness, territorial defense, or what we call an “all-clear” signal, and is used in a variety of contexts. Some common situations which may elicit a jump-yip include:

- When a prairie dog is startled either by a noise or sudden movement nearby

- Upon perceiving and running away from a snake (accompanied by foot-thumping) (see THE PREY ANIMAL)

- Immediately after a perceived predator or danger has passed or disappeared from view (called the "all-clear")

- When two prairie dogs break from a territorial dispute

Upon witnessing a jump-yip, coterie members will immediately go into alert mode, and will often even join in a chorus of jump-yips, in which they are either responding to the original call or to the threat which elicited the original call. This display is not seen in the white-tail group (white-tailed, Utah, and Gunnison's prairie dogs), and the reasons for this may vary; there may be a correlation between the higher sociality and coloniality seen in black-tailed prairie dogs and the use of this display to communicate with a more dense population.

The Territorial call

The most common of all prairie dog vocalizations, the territorial call is multi-purpose and variable. For the white-tail group (the white-tailed, Utah, and Gunnison's species) the territorial call can be described as a laughing bark, a staccato call, or a raspy chatter. For the black-tailed prairie dog and Mexican prairie dog (the black-tail group), the territorial call is the famous "jump-yip" call described above. Among white-tailed and Utah prairie dogs, territorial calls are sometimes accompanied by a throw-back of the head, so that it looks like the prairie dog is calling at the sky.

Territorial calls can serve to communicate different messages, and are given contextually. Usually upon first waking in the morning, prairie dogs will give a territorial call as a sort of roll-call to check if anyone else is awake - the same goes for the territorial call just before submerging for the night. Territorial calls are also given "seemingly" at random throughout the day as a way of saying, "This is my territory and I will defend it from intruders." During territorial disputes and often after one dog chases another into a burrow, territorial calls are emitted frequently.

The video below shows the Gunnison's prairie dog territorial call, and demonstrates differences among individuals despite the vocalizations being the same call.

The photos below show prairie dogs giving territorial calls. By learning what we're looking for in posture and context, researchers can see what is being vocalized even when the prairie dog is too far to hear.

the Alarm / antipredator Call

As an Order, rodents have the distinction of being prey to anything that can catch and eat them, which makes the prairie dog’s list of potential predators across North America quite long indeed. But being small and conspicuous does not mean the prairie dog is easy to catch. A predator must surprise not only the individual they are after, but every prairie dog in the vicinity. Despite the safety in numbers and the vigilance of the clan and colony, however, predations are common and inevitable.

The prairie dog was so-called by American colonialists for its iconic alarm call - the sharp, steady barks carrying over the grassland.

Researchers have given the prairie dog’s antipredator call all sorts of interesting names: alarm note (Merriam 1902), squit-tuck (Seton 1926), warning bark (King 1955), alarm bark (Smith 1967), barks (Smith et al 1977), repetitious bark (Waring 1970), vocal alarm (Hoogland 1981a)” – The Black-tailed Prairie Dog, J.L. Hoogland, 1995

Also known as the anti-predator call, the alarm call is the same across all species, though sometimes different individuals may sound different when they give the same call (almost like a variation in voices or intonation). The alarm call is simple, loud, and highly effective. The sharp, repetitive bark resounds for quite a distance, making it equally audible to the predator, who could easily identify the caller in the colony. It is known that alarm calling can often make the caller more vulnerable to predation, essentially calling attention to itself. So why do it? Because the primary advantage to coloniality is shared vigilance against predators, and those giving alarm calls are helping their kin to survive, thus ensuring genetic survival.

An anti-predator call resounds across the area to assure that all the clan/coterie members will not miss the alert. Interestingly, prairie dogs listening to an alarm call nearby can distinguish how far a caller is from them, and will likely only respond if the alert is coming from their own clan or immediate area. While false alarms are not uncommon, most alarms are only let out when a threat appears imminent. False alarms may occur if a prairie dog sees something moving in the grass and cannot immediately identify it, or if a human or domestic animal approaches and the prairie dog is unsure if there is true danger. Typically, false alarms are brief and not taken up by other callers as readily. True alarms are more likely to last longer, and be taken up by a chorus of other callers.

Alarm calls can have variations in intensity and speed which have been the topic of intense research. The purpose of the alarm call is to warn both immediate and in some cases distant kin of a perceived threat, and thus the call has to be direct, loud, and communicative. Depending on the degree of threat, some calls may last a couple of seconds, while others may last many minutes and even up to an hour. Longer calls are more likely to be taken up by a chorus of other callers in the same clan, as they hear the alarm and become alert and therefore perceive the threat themselves. As a predator comes closer, the call may intensify in speed. When a predator is found out, they will often halt their approach and eventually walk away. As the threat recedes, so does the intensity, volume, and speed of the alarm calls.

Watching prairie dogs alarm calling, you will find them either alert on all four legs, more commonly standing tall on their hind legs, or peeking their heads or upper bodies out from burrow entrances. Retreating underground into their burrows is a last-resort tactic for the prairie dog; rather, when danger is perceived, prairie dogs will sometimes run to their burrows but remain on the mound or partially in the burrow entrance, still able to see what is going on aboveground. If the predator comes too close and gives them no choice, the prairie dog will retreat into its burrow, but it could be many minutes to hours before that prairie dog will emerge again. When every day and every hour of foraging and interacting is important to the prairie dog, losing time underground is to be avoided as much as possible.

The Mating Call

As the name suggests, the mating call is strictly a mating season vocalization. Understanding all of the behaviors that go into copulating on the day a female is in estrus is critical to differentiating a mating call from an alarm call, as to the naked ear the two vocalizations sound identical. But mating calls are only given in relation to copulation, wherein the male is standing at or near the entrance to the mating burrow and the female is either beside him or is in the burrow already. The mating call may be given before copulation occurs, or after when the male emerges from the copulation. Mating calls are not given by every male; nor does the same male call for every female - and these nuances are still not well understood. The call may last several seconds or many minutes, as the video below demonstrates.

A mating call after copulation. ©John Hoogland 2012

A mating call before copulation, with the estrous female still aboveground. ©John Hoogland 2009

Other Vocalizations

In addition to the calls above-mentioned, prairie dogs use their voices to communicate smaller messages to each other during interactions. Some of these sounds, like the chirp or squeaks a mother makes to her offspring when she wants them to follow her to a new burrow, are very quiet and difficult for researchers to hear. Other sounds, like the protest squeaks (or screams, if you will) a prairie dog lets out when it is being chased or buried, are loud and clear. Sometimes during a hostile kiss, the receiver of the kiss will let out a squeak and jump away. Lastly, though this is not a vocalization per se, during territorial disputes angry prairie dogs will clatter their teeth together to express their ire (sometimes quite loudly) and so communicate their displeasure audibly.

Whatever vocalizations occur underground between prairie dogs are yet to be explored fully, especially in situ (in the wild), giving us more to look forward to as technologies further our research in prairie dog communication.